-

France

France – Sudden termination of international contract

17 June 2024

- Contracts

Article 442-1.II of the French Commercial Code (former Article L. 442-6.I.5 °) sanctions the termination by a trader of a written contract or an informal business relationship without giving sufficient written prior notice. Over the last twenty years, this article became the recurring legal basis for all compensation actions (up to 18 months of gross margin, plus other damages) when a commercial relationship or a contract ends (totally or even partially).

Therefore, a foreign trader who contracts with a French company should try not to fall under the aegis of this rule (part I) and, if it cannot, should understand and control its implementation (part II).

In a nutshell:

How can a foreign company avoid or control the risk linked to the “sudden termination of commercial relations” set by French law? Foreign companies doing business with a French counterpart should:

– enter, as soon as possible, into a written (frame) agreement with their French suppliers or customers, even for a very simple relation and;

– stipulate a clause in favour of foreign court or arbitration and foreign applicable law while, failing to choose it, they would rather be subject to French courts and laws;

How can a foreign company master the risk linked to the “sudden termination of commercial relations” set by French law? Foreign companies doing business with a French counterpart should:

- know that this article applies to almost all type of commercial relationship or contracts, whether written or not, fixed-term or not;

- check whether its relation/contract is sufficiently long, regular and significant and whether the other party has a legitimate belief in the continuation of this relation/contract;

- give a written notice of termination or non-renewal (or even of a major modification), which length takes mainly into account the duration of the relation, irrespectively of the length of the contractual notice;

- invoke, with cautiousness, force majeure and gross negligence of the party, to set aside “sudden termination”;

- anticipate, in case of insufficient notice, a compensation which amount is the product of the average monthly gross margin per the length of non-granted prior notice.

How to avoid the application of the French “Sudden Termination” rule?

In international matters, a foreign company must anticipate whether its relationship will be subject or not to French law before terminating a contract or a business relationship and, in case of dispute, whether it will be brought before a French court or not.

What will be the law applicable to “Sudden Termination”?

It is quite difficult for a foreign company to correctly grasp the French legal framework of conflict of laws rules applicable to “sudden termination”. In a ruling of September 19, 2018 (RG 16/05579, DES/ Clarins), the Court of appeal of Paris made, by an implicit reference to the Granarolo EU ruling (07 14 16, N°C196/15) an extension of the contractual qualification to most of the business relationships which will improve foreseeability in order for a foreign company to try to exclude French law and its “sudden termination” rule.

Sudden termination of a written contract or of a “tacit contractual relationship”

According to Rome I Regulation (EC No 593/2008, June 17 2008) on the law applicable to contracts:

– In case of choice of a foreign law by the parties: The clause selecting a foreign applicable law will be valid and respected by French judges (subject to OMR, see below), provided that the choice of law by the parties is express or certain.

– In case of no choice by the parties: French law will likely to be declared applicable as it might be either the law of the country where is based the distributor/franchisee, etc. or the law of the country where the party who is to provide the service features of the contract has its domicile.

Sudden termination of a “non-tacit contractual relationship”

In case of informal relationship (i.e. orders placed from time to time), French judges would retain the tort qualification and will refer to the Rome II Regulation (No 864/2007, July 11 2007) on the law applicable to non-contractual obligations..

– In case of choice of a foreign law by the parties: a properly drafted choice of foreign law clause should be implemented by a French judge, provided that it expressly includes tort cases.

– In case of no choice of law by the parties: French law will likely to be declared applicable as it might be the law of the country where the damage occurs (regardless of the place of the causing event or that of the indirect consequences), which is the place of the head office where the French victim suffers the consequences of the termination.

“Sudden Termination” rule, a French Overriding Mandatory Rule?

The position of French courts is quite vague and unsatisfactory, and this has been the case for a long time. To make it short: the Commercial Court of Paris judges that “sudden termination” is not an OMR, the Court of appeal of Paris (sole French appellate court in charge of “sudden termination” cases) is also not in favour of the OMR qualification on the grounds that the text “protects purely private economic interests” (CA Paris, pôle 5, ch. 5, Feb 28. 2019, n° 17/16475 / CA Paris, pôle 5, ch. 5, Oct 8. 2020, n°17/19893). Recently, the Paris Court of Appeal reaffirmed that the rules on sudden termination of established commercial relations are not an OMR (Court of appeal Paris, March 11, 2021, n° 18/03112).

The French Supreme Court has never explicitly addressed the issue (OMR or not OMR). Indeed, the French Supreme Court ruled in the Expedia case (Cass. com., July 8, 2020, n°17-31.536) that the provisions of the former article L. 442-6, I, 2º and II, d), about “significant imbalance” (which is in the same set of rules than “Sudden termination”) are OMR. However, this qualification should be limited to the specific action brought by the Ministry of Finance and not be applicable to an action by a private party. Moreover, some courts may be tempted to invoke the provisions of French law n°2023-221 (March 30, 2023, aka Egalim III) to qualify Sudden termination rule as an OMR, however this text (article L 444-1.A Commercial code) does not quote expressly OMR and set no justification whatsoever to set such a qualification.

Consequently, if a claim for “sudden termination” is brought to a French court, there is still a risk that the latter would exclude the applicable foreign law and replace it with the regime resulting from the “sudden termination” of Article L 442-1. II. However, to avoid this risk, a foreign company would better not only choose a foreign governing law but also stipulate that the dispute will be brought before a foreign judge or an arbitral tribunal.

How to avoid jurisdiction of French court over a “Sudden Termination” claim?

“Sudden Termination” claim and intra EU co-contractor

The ECJ ruling (Granarolo, July 14, 2016, N°C196/15) created a distinction between claims occurring from:

– written framework contract or tacit contractual relationship (existing only if the body of evidences listed by the ECJ are identified by national judges, i.e. length of relation and commitments recognized to each other, such as exclusivity, special price or terms of delivery or payment, non-competition, etc.): such claim has a contractual nature according to conflict of jurisdiction rules under Brussels I recast Regulation;

– informal relationship which is a non–tacit contractual relationship (i.e. orders placed from time to time): such a request has a tort nature under Brussels I recast ;

To be noted: the so-called Egalim III law has no impact on the EU rules on jurisdiction clauses.

(a) Who is the Judge of the “sudden termination” of a written contract or of a “tacit contractual relationship”?

– Jurisdiction clause for the benefit of a foreign court will be enforced by French courts, even though it is an asymmetrical clause (Court of cassation, October 7, 2015, Ebizcuss.com / Apple Sales International).

– In case of lack of choice of court clause, French courts are likely to have jurisdiction if the French claimant bringing a case based on “sudden termination» is the service provider, such as distributor, agent, etc. (see ECJ Corman Collins case, 19 12 13, C-9/12, and article 7.1.b.2 of Brussels I recast°).

(b) Who is the Judge of the “sudden termination” of a “non- tacit contractual relationship”?

– We believe that French courts may continue to give effect to a jurisdiction clause in tort case, especially when it expressly encompasses tort litigation (Court of cassation, 1° Ch. Civ., January 18, 2017, n° 15-26105, Riviera Motors / Aston Martin Lagonda Ltd).

– In case of lack of choice of court clause, French courts will have jurisdiction over a “sudden termination” claim as the judge of the place where the harmful event occurred (art. 7.3 of Brussels I recast), which is the place where the sudden termination has effect…i.e. in France if the French company is the victim.

“Sudden Termination” claim and Non-EU co-contractor

The Granarolo solution will not ipso facto apply if a French victim brings a claim to French courts, based on a “sudden termination” made by a non-EU company. In non-EU relations, French judges could continue to retain only the tort qualification. In such a case, French courts may keep their jurisdiction based on the place where the harmful event occurs.

Jurisdiction clause to a foreign court may be recognized in France (even for tort-based claims), provided that this jurisdiction clause is valid according to either a bilateral international convention or to the Hague Convention of 30 June 2005 on choice of court agreements. Otherwise, according to Egalim III law, imperative jurisdiction might be attributable to French courts.

“Sudden Termination” claim and arbitration

Stipulating an ad hoc or institutional arbitration clause is probably the safest solution to avoid the jurisdiction of French courts. Ideally, the clause will fix the seat of the arbitral tribunal outside France. According to the principle of competence-competence of the arbitrators, French courts declare themselves incompetent, unless the arbitration clause is manifestly void or manifestly inapplicable, regardless of contract or tort ground (see, in particular, Paris Court of Appeal, 5 September 2019, n°17/03703). The so-called “Egalim III” law has no impact on arbitration clauses.

Conclusion: Foreign companies should not leave open the Jurisdiction and governing Law issues. They must negotiate a safe harbour, otherwise a French victim of a termination will likely to be entitled to bring a “sudden termination” claim in front of French judges (see what happen below in Part 2)

How to master the “Sudden Termination” French rules?

When French law is applicable, the foreign company will face the legal regime of article L442 -1.II of the French Commercial Code sanctioning “sudden termination”. As a preliminary remark, it is important to know, above all, that the implementation of the liability for “sudden termination” is the consequence of the lack of a notice or a too short notice. Thus, this scheme does not lay down an automatic compensation rule. In other words, as soon as reasonable notice is given by the author of the termination, liability on that basis can be dismissed.

The prerequisite for “Sudden Termination”: an established commercial relationship

All contracts are covered by this legal regime, except for contracts whose regulations provide for a specific notice of termination, like commercial agency contracts and transport of goods by road subcontracts.

First, there must be a relationship that can be proven by a written contract or de facto, by behaviour of the parties. Article L.442-1 II of the French Commercial Code covers all “commercial” relationships and not only “contractual ones so that such relationship may be based on a succession of tacitly renewed contracts or a regular flow of business, materialized by multiple orders. This was recently recalled by the Supreme Court (Supreme Court, February 16, 2022, n° 20-18.844)

Second, this relationship must have an established character. There is no legal definition, but this notion has been defined year after year by case law which has established an objective criterion and a more subjective one.

(a) The objective criterion implies a sufficiently long, regular and significant relationship between the two parties. The duration of the relationship is the most important criterion. The relationship must also be regular, that is, it must not have been interrupted (too often or too long). The relationship must ultimately be meaningful and represent a serious flow of business between the parties, in volume or value.

(b) The subjective test focuses primarily on the legitimate belief of the victim of the rupture in the continuation of the contract / the relationship that is based on factual elements, such as investment requests, budgets over several years, etc. Conversely, it is on the basis of the finding of a lack of legitimate belief in a common future that the terminating party can prove the absence of a stable character when he has resorted, on several occasions, a call for tenders (unless it is a trick).

Anticipating a “Sudden Termination” claim

(a) The termination may be total or partial

The total rupture is materialized by a complete stop of the relations, for example ending the contract, stopping the sending of orders by the purchaser or the recording of orders by the supplier.

The Supreme Court recently recalled that a significant drop in sales with a partner must be considered as a partial rupture of the relationship (February 16, 2022, n° 20-18.844, cited above). But the most complicated situation to deal with is the so-called partial rupture that will be deduced from a modification of elements that partly impacts the relationship but does not reduce it to nothing (ex.: a price increase or decrease, a change in the terms of payment or delivery).

(b) The termination must be subject to a reasonable written prior notice

The notice must be notified in writing. The absence of written notice is already a breach in itself. The notification must clearly reflect the willingness of a party to sever the relationship in whole or in part, which must be clearly identified. The notification must also clearly identify the date on which the relationship will end.

Thus, an ambiguity on the notice period (e.g if the termination of an agreement is notified, whilst offering to maintain certain prices and payment terms, in the meantime) is considered as an insufficient termination notice (French Supreme Court, January 29, 2013, n° 11-23.676).

Parties must distinguish between the letter of formal notice for default and the subsequent notification of the breach, giving notice (if applicable). During the period of notice, parties must fully comply with all contractual conditions.

This principle also applies to distribution contracts subject to specific French rules imposing annual or multi-year negotiation obligations. In fact, the Court of cassation has ruled that “when the conditions of the commercial relationship established between the parties are subject to annual negotiation, modifications made during the notice period which are not so substantial as to undermine its effectiveness do not constitute a brutal breach of that relationship” (Cass. com., Dec. 7, 2022, n° 19-22.538).

However, it’s not necessary to mention the reasons why the commercial relationship is terminated is not a fault or breach of the relationship. In fact, French courts consider that “the fact that the given reason to terminate was false does not in any way present the terminating party from terminating the commercial relationship” (Versailles Court of Appeal, June 10, 1999).

The duration of the prior notice to be respected is not defined by French law which did not pose precise rule until the reform 2019. If several criteria are stated by case law, it should be noted that the most important criterion is the duration of the relationship. Judges also take into account the share of turnover achieved by the victim, the existence or not of a territorial exclusivity, the nature of the products and the sector of activity, the importance of the investments made by the victim especially to the relationship in question, and finally the state of economic dependence. Economic dependence is defined as the impossibility for a company to have a solution that is technically and economically equivalent to the contractual relations it has established with another company. Case law considers this to be an aggravating factor justifying a longer termination notice.

The minimum notice period must be notified at the time of notification of termination. As a consequence, events that affect the victim after the notification, both positively (conclusion of a new contract) and negatively (loss of another custome), will not be taken into account by the judge, at the time of ruling, when assessing the “brutality” of the termination.

The length of the notice given by the judges is very variable. The appreciation of notice is made on a case-by-case basis. It is very difficult to give a golden rule, even though roughly for each year of relationship, a month’s notice might be due (to modulate up or down depending on the other criteria in the relationship). But way of illustration, however, the following case law may be cited:

- Paris Court of Appeal , Feb.9, 2022: 16-year relationship with 15 months’ notice;

- Paris Court of Appeal, Jan.20, 2022: 12-year relationship with 8 months’ notice;

- Paris Court of Appeal, Oct. 25, 2022: 16-year relationship with 18 months’ notice;

- Paris Court of Appeal , Feb. 23, 2022: 17-year relationship with 11 months’ notice;

- Paris Court of Appeal, Sept. 21, 2022: 5-year relationship with 14 months’ notice.

Since the Order of April 24, 2019, which limits the length of reasonable notice to a maximum of 18 months, if the notice period granted by a party is 18 months, it cannot be held liable for a sudden termination. However, much of the litigation remains uncertain, as only exceptionally long or particularly sensitive relationships led, prior to 019, to the award of more than 18 months’ notice. Ordinance of April 24, 2019, limits to 18 months the maximum period of notice reasonably due under Article L 442-1.II. But much of the litigation will remain uncertain since only relations of exceptional longevity or particularly sensitive, could have led to the allocation of a notice higher than 18 months.

Judges are not bound by the contractual notices stipulated in the contract. But if the author of the breach also violated the terms and conditions of termination provided for by contract, the victim may seek the responsibility of the author both on the tort basis of the sudden rupture and also on the basis of the breach of a contractual obligation.

Cases in which “Sudden Termination” is ruled out

The legal regime provides for two cases, and the case-law seems to have imposed others.

(a) The two legal exceptions are Force majeure (very rarely consecrated by the courts) and the fault of the victim of the termination, case-law having added that it must be a serious violation (“faute grave”) of a contractual commitment or a legal provision (such as non-respect of an exclusivity, a non-compete, a confidentiality or a change of control duty, or non-payment of amounts due contractually).

The judges consider themselves, of course, not bound by a termination clause defining what constitutes serious misconduct. In any case the party who terminates for serious misconduct must clearly notify it in its letter of termination. Above all, serious misconduct leads to a lack of notice, therefore, if the terminating party alleges serious misconduct but grants notice, whichever it may be, judges may conclude that the fault was not serious enough.

Thus, the seriousness of the misconduct must be motivated by judges in their rulings. Noting that the contract was breached after two formal notices is not sufficient (Cass. com., Feb 16. 2022, n° 20-18.844).

However, the Court of Cassation considers that “even in the case of serious misconduct justifying the immediate termination of the commercial relationship, the other party remains free to give the other party a notice” (Cass. Com., Oct. 14 2020, n°18-22.119).

(b) In recent years, case-law has added other cases of liability waiver. This is the case when the rupture is the consequence of a cause external to the author of the rupture, such as the economic crisis, the loss of its own customers or suppliers, upstream or downstream.

For example, in 2021 the Court of cassation has ruled that “the business partner is not entitled to an unchanged relationship and cannot refuse any adaptation required by economic changes” (Com, Dec 01, 2021, n°20-19.113). In fact, to be attributable to an economic player, a termination must be free and deliberate. This is not the case if termination is imposed by the economic situation.

However, adding a liability exemption clause in a contract, aimed at waiving destinated to escape the penalties of article L. 442-1, is without consequences on the judge’s appreciation.

Judges have also excluded “sudden termination” in the hypothesis of the end of the first period of a fixed-term contract, whatever its duration is: the first renewal of a contract, constitutes a foreseeable event for the victim of the rupture, which excludes the very notion of brutality; but once the contract has been renewed at least once, judges can subsequently characterize the victim’s legitimate belief in a new tacit renewal.

Compensation for “Sudden Termination”

Judges only compensate for the detrimental consequences of the brutality itself of the breach but do not compensate, at least in the context of article L442 -1.II, for the consequences of the breach itself.

The basic rule is very simple: it is necessary to determine the length of the notice which should have been granted, from which the notice actually granted is deducted. This net notice is multiplied by the average monthly gross margin of the victim, or more often the so called margin on variable costs (i.e. the turnover minus costs disappearing with non-performance of the contract/relation). Defendant should not hesitate to ask for the full accountancy evidences, especially to identify (lower) margin rates, or even for a judicial expertise on those accounting elements. In general, the base of the average monthly margin consists of the last 24 or 36 months.

The compensation calculated on the average margin is, in general, exclusive of any other compensation. However, the victim can prove that it has suffered other losses as a consequence of the brutality of the rupture. Such as dismissals directly caused by this brutality or the depreciation of investments made recently by the victim.

Some practical tips when considering to anticipate “Sudden Termination”

Even though the legal regime is still ambiguous and the case-law terribly casuistic which prevents to release strong guidelines, here are some practical tips when a company plans to terminate a relationship / contract:

- in the case of a fixed-term contract renewable tacitly, the notification of non-renewal must be anticipated well in advance of the beginning of the contractual notice in order to avoid being in a situation where it is necessary to choose between not renewing the contract with a notice that is not sufficient or agree to see the contract renewed itself for a new term;

- commercial teams must be made aware of the risk of partial sudden termination when they change the conditions of execution of a commercial relationship / contract too radically;

- in some cases, it may be useful to send a pre-notice of termination with a “notice proposal” in order to try to validate this notice with the other party;

- it may also be useful, in certain relationships, to notify the end of the relationship with different lengths of notice depending on the nature of the product lines;

- Finally, the best way is to conclude an end-of-relation protocol, fixing the duration of the notice as well as, if necessary, the progressive decline of the orders, the whole within the framework of a settlement agreement which definitively waives any claim, including “sudden termination”.

Sudden termination regime shall be taken into consideration when entering into the final phase of a duration relationship: the way in which the contract (or de facto relationship) is terminated must be carefully planned, in order to manage the risk of causing damages to the counterparty and being sued for compensation.

Given the significance of the influencer market (over €21 billion in 2023), which now encompasses all sectors, and with a view for transparency and consumer protection, France, with the law of June 9, 2023, proposed the world’s first regulation governing the activities of influencers, with the objective of defining and regulating influencer activities on social media platforms.

However, influencers are subject to multiple obligations stemming from various sources, necessitating the utmost vigilance, both in drafting influence agreements (between influencers and agencies or between influencers and advertisers) and in the behaviour they must adopt on social media or online platforms. This vigilance is particularly heightened as existing regulations do not cover the core of influencers’ activities, especially their status and remuneration, which remain subject to legal ambiguity, posing risks to advertisers as regulatory authorities’ scrutiny intensifies.

Key points to remember

- Influencers’ activity is subject to numerous regulations, including the law of June 9, 2023.

- This law not only regulates the drafting of influence contracts but also the influencer’s behaviour to ensure greater transparency for consumers.

- Every influencer whose audience includes French users is affected by the provisions of the law of June 9, 2023, even if they are not physically present in French territory.

- Both the law of June 9, 2023, and the “Digital Services Act,” as well as the proposed law on “fast fashion,” foresee increasing accountability for various actors in the commercial influence sector, particularly influencers and online platforms.

- Despite a plethora of regulations, the status and remuneration of influencers remain unaddressed issues that require special attention from advertisers engaging with influencers.

The law of June 9, 2023, regulating influencer activity

The definition of influencer professions

The law of June 9, 2023, provides two essential definitions for influencer activities:

- Influencers are defined as ‘natural or legal persons who, for consideration, mobilize their notoriety with their audience to communicate to the public, electronically, content aimed at promoting, directly or indirectly, goods, services, or any cause, engaging in commercial influence activities electronically.’

- The activity of an influencer agent is defined as ‘that which consists of representing, for consideration,’ the influencer or a possible agent ‘with the aim of promoting, for consideration, goods, services, or any cause‘ (article 7) The influencer agent must take ‘necessary measures to ensure the defense of the interests of the persons they represent, to avoid situations of conflict of interest, and to ensure the compliance of their activity‘ with the law of June 9, 2023.

The obligations imposed on commercial messages created by the influencer

The law sets forth obligations that influencers must adhere to regarding their publications:

- Mandatory particulars: When creating content, this law imposes an obligation on influencers to provide information to consumers, aiming for transparency towards their audience. Thus, influencers are required to clearly, legibly, and identifiably indicate on the influencer’s image or video, regardless of its format and throughout the entire viewing duration (according to modalities to be defined by decree):

– The mention “advertisement” or “commercial collaboration.” Violating this obligation constitutes deceptive commercial practice punishable by two years’ imprisonment and a fine of €300,000 (Article 5 of the law of June 9, 2023).

– The mention of “altered images” (modification by image processing methods aimed at refining or thickening the silhouette or modifying the appearance of the face) or “virtual images” (images created by artificial intelligence). Failure to do so may result in a one-year prison sentence and a fine of €4,500 (Article 5 of the law of June 9, 2023).

- Prohibited or regulated promotions: This law reminds certain prohibitions, subject to criminal and administrative sanctions, stemming from French law on the direct or indirect promotion of certain categories of products and services, under penalty of criminal or administrative sanctions. This includes the promotion of products and services related to:

– health: surgery, aesthetic medicine, therapeutic prescriptions, and nicotine products;

– non-domestic animals, unless it concerns an establishment authorized to hold them;

– financial: contracts, financial products, and services;

– sports-related: subscriptions to sports advice or predictions;

– crypto assets: if not from registered actors or have not received approval from the AMF;

– gambling: their promotion prohibited for those under 18 years old and regulated by law;

– professional training: their promotion is not prohibited but regulated.

The accountability of influencer behaviour

The law also holds influencers accountable from the contracting of their relationships and when they act as sellers:

- Regulation of commercial influence agreements: This law imposes, subject to nullity, from a certain threshold of influencer remuneration (defined by decree), the formalization in writing of the agreement between the advertiser and the influencer, but also, if applicable, between the influencer’s agent, and the mandatory stipulation of certain clauses (remuneration, mission description, etc.).

- Influencer responsibility as a cyber seller: Influencers engaging in drop shipping (selling products without handling their delivery, done by the supplier) must provide the buyer with all information in French as required by Article L. 221-5 of the Consumer Code about the product, such as its availability and legality (i.e., guarantee that the product is not counterfeit), applicable product warranty, and supplier identity. Additionally, influencers must ensure the proper delivery and receipt of products and, in case of default, compensate the buyer. Influencers are also logically subject to obligations regarding deceptive commercial practices (for more information, the DGCCRF website explain the dropshipping).

The accountability of other actors in the commercial influence ecosystem

Joint and several liability is set by law, for the advertiser, influencer, or influencer’s agent for damages caused to third parties in the execution of the commercial influence contract, allowing the victim of the damage to act against the most solvent party.

Furthermore, the law introduces accountability for online platforms by partially incorporating the European Regulation 2022/2065 on digital services (known as the “DSA“) of October 19, 2022.

French regulation and international influencers

Influencers established outside the European Union (including also Switzerland and the EEA) who promote products or services to a French audience must obtain professional liability insurance from an insurer established within the EU. They must also designate a legal or natural person providing “a form of representation” (SIC) within the EU. This representative (whose regime is not very clear) is remunerated to represent the influencer before administrative and judicial authorities and to ensure the compliance of the influencer’s activity with law of June 9, 2023.

Furthermore, according to law of June 9, 2023, when the contract binding the influencer (or their agency) aims to implement a commercial influence activity electronically “targeting in particular an audience established in French territory” (SIC), this contract should be exclusively subject to French law (including the Consumer Code, the Intellectual Property Code, and the law of June 9, 2023). According to this law, the absence of such a stipulation would be sanctioned by the nullity of the contract. Law of June 9, 2023, seems to be established as an overriding mandatory law capable of setting aside the choice of a foreign law.

However, the legitimacy (what about compliance with the definition of overriding mandatory rules established by Regulation Rome I?) and effectiveness (what if the contract specifies a foreign law and a foreign jurisdiction?) of such a legal provision can be questioned, notably due to its vague and general wording. In fact, it should be the activity deployed by the “foreign” influencer to their community in France that should be apprehended by French overriding mandatory rules, rather than the content of the agreement concluded with the advertiser (which itself could also be foreign, by the way).

The other regulations governing the activity of influencers

The European regulations

The DSA further holds influencers accountable because, in addition to the reporting mechanism imposed on platforms to report illicit content (thus identifying a failing influencer), platforms must ensure (and will therefore shift this responsibility to the influencer) the identification of commercial communications and specific transparency obligations towards consumers.

The «soft law»

As early as 2015, the Advertising Regulatory Authority (“ARPP”) issued recommendations on best practices for digital advertising. Similarly, in March 2023, the French Ministry of Economy published a “code of conduct” for influencers and content creators. In 2023, the European Commission launched a legal information platform for influencers. Although non-binding, these rules, in addition to existing regulations, serve as guidelines for both influencers and content creators, as well as for judicial and administrative authorities.

The special status of child influencers

The law of October 19, 2020, aimed at regulating the commercial exploitation of children’s images on online platforms, notably opens up the possibility for child influencers to be recognized as salaried workers. However, this law only targeted video-sharing platforms. Article 2 of the law of June 9, 2023, extended the provisions regarding child influencer labor introduced by the 2020 law to all online platforms. Finally, a recent law aimed at ensuring respect for the image rights of children was published on February 19, 2024, introducing a principle of joint and several responsibility of both parents in protecting the minor’s image rights.

The status and remuneration of influencers: uncertainty persists

Despite the diversity of regulations applicable to influencers, none address their status and remuneration.

The status of the influencer

In the absence of regulations governing the status of influencers, a legal ambiguity persists regarding whether the influencer should be considered an independent contractor, an employee (as is partly the case for models or artists), or even as a brand representative (i.e. commercial agent), depending on the missions contractually entrusted to the influencer.

The nature of the contract and the applicable social security regime stem from the missions assigned to the influencer:

- In the case of an employment contract, the influencer will fall under the general regime for employees and assimilated persons, based on Articles L. 311-2 or 311-3 of the French Social Security Code.

- In the case of a service contract, the influencer will fall under the regime for self-employed workers.

The existence of a relationship of subordination between the advertiser and the influencer typically determines the qualification of an employment contract. Subordination is generally characterized when the employer gives orders and directives, has the power to control and sanction, and the influencer follows these directives. However, some activities are subject to a presumption of an employment contract; this is the case (at least in part) for artist contracts under Article L. 7121-3 of the French Labor Code and model contracts under Article L. 7123-2 of the French Labor Code.

The remuneration of the influencer

The influencer can be remunerated in cash (fixed or proportional) and/or in kind (for example: receiving a product from the brand, invitations to private or public events, coverage of travel expenses, etc.). The influencer’s remuneration must be specified in the influencer agreement and is directly impacted by the influencer’s status, as certain obligations (minimum wage, payment of social security contributions, etc.) apply in the case of an employment contract.

Furthermore, the remuneration (for the influencer’s services) must be distinguished from that of the transfer of their copyrights or image rights, which are subject to separate remuneration in exchange for the IP rights transferred.

The influencers… in the spotlight

The law of June 9, 2023, grants the French authority (i.e. the Consumer Affairs, Competition and Fraud Prevention Agency, “DGCCRF”) new injunction powers (with reinforced penalties). This comes in addition to the recent creation of a “commercial influence squad“, within the DGCCRF, tasked with monitoring social networks, and responding to reports received through Signal Conso. The law provides for fines and the possibility of blocking content.

As early as August 2023, the DGCCRF issued warnings to several influencers to comply with the new regulations on commercial influence and imposed on them the obligation to publicly disclose their conviction for non-compliance with the new provisions regarding transparency to consumers on their own social networks, a heavy penalty for actors whose activity relies on their popularity (DGCCRF investigation on the commercial practices of influencers).

On February 14, 2024, the European Commission and the national consumer protection authorities of 22 EU member states, Norway, and Iceland published the results of an analysis conducted on 570 influencers (the so-called “clean-up operation” of 2023 on influencers): only one in five influencers consistently presented their commercial content as advertising.

In response to environmental, ethical, and quality concerns related to “fast fashion,” a draft law aiming to ban advertising for fast fashion brands, including advertising done by influencers (Proposal for a law aiming to reduce the environmental impact of the textile industry), was adopted by the National Assembly on first reading on March 14, 2024.

Lastly, the law of June 9, 2023, has been criticized by the European Commission, which considers that the law would contravene certain principles provided by EU law, notably the principle of “country of origin,” according to which the company providing a service in other EU countries is exclusively subject to the law of its country of establishment (principle initially provided for by the E-commerce Directive of June 8, 2000, and included in the DSA). Some of its provisions, particularly those concerning the application of French law to foreign influencers, could therefore be subject to forthcoming – and welcome – modifications.

Summary

To avoid disputes with important suppliers, it is advisable to plan purchases over the medium and long term and not operate solely on the basis of orders and order confirmations. Planning makes it possible to agree on the duration of the ‘supply agreement, minimum volumes of products to be delivered and delivery schedules, prices, and the conditions under which prices can be varied over time.

The use of a framework purchase agreement can help avoid future uncertainties and allows various options to be used to manage commodity price fluctuations depending on the type of products , such as automatic price indexing or agreement to renegotiate in the event of commodity fluctuations beyond a certain set tolerance period.

I read in a press release: “These days, the glass industry is sending wine companies new unilateral contract amendments with price changes of 20%…”

What can one do to avoid the imposition of price increases by suppliers?

- Know your rights and act in an informed manner

- Plan and organise your supply chain

Does my supplier have the right to increase prices?

If contracts have already been concluded, e.g., orders have already been confirmed by the supplier, the answer is often no.

It is not legitimate to request a price change. It is much less legitimate to communicate it unilaterally, with the threat of cancelling the order or not delivering the goods if the request is not granted.

What if he tells me it is force majeure?

That’s wrong: increased costs are not a force majeure but rather an unforeseen excessive onerousness, which hardly happens.

What if the supplier canceled the order, unilaterally increased the price, or did not deliver the goods?

He would be in breach of contract and liable to pay damages for violating his contractual obligations.

How can one avoid a tug-of-war with suppliers?

The tools are there. You have to know them and use them.

It is necessary to plan purchases in the medium term, agreeing with suppliers on a schedule in which are set out:

- the quantities of products to be ordered

- the delivery terms

- the durationof the agreement

- the pricesof the products or raw materials

- the conditions under which prices can be varied

There is a very effective instrument to do so: a framework purchase agreement.

Using a framework purchase agreement, the parties negotiate the above elements, which will be valid for the agreed period.

Once the agreement is concluded, product orders will follow, governed by the framework agreement, without the need to renegotiate the content of individual deliveries each time.

For an in-depth discussion of this contract, see this article.

- “Yes, but my suppliers will never sign it!”

Why not? Ask them to explain the reason.

This type of agreement is in the interest of both parties. It allows planning future orders and grants certainty as to whether, when, and how much the parties can change the price.

In contrast, acting without written agreements forces the parties to operate in an environment of uncertainty. Suppliers can request price increases from one day to the next and refuse supply if the changes are not accepted.

How are price changes for future supplies regulated?

Depending on the type of products or services and the raw materials or energy relevant in determining the final price, there are several possibilities.

- The first option is to index the price automatically. E.g., if the cost of a barrel of Brent oil increases/decreases by 10%, the party concerned is entitled to request a corresponding adjustment of the product’s price in all orders placed as of the following week.

- An alternative is to provide for a price renegotiation in the event of a fluctuation of the reference commodity. E.g., suppose the LME Aluminium index of the London Stock Exchange increases above a certain threshold. In that case, the interested party may request a price renegotiationfor orders in the period following the increase.

What if the parties do not agree on new prices?

It is possible to terminate the contract or refer the price determination to a third party, who would act as arbitrator and set the new prices for future orders.

Summary

The framework supply contract is an agreement that regulates a series of future sales and purchases between two parties (customer and supplier) that take place over a certain period of time. This agreement determines the main elements of future contracts such as price, product volumes, delivery terms, technical or quality specifications, and the duration of the agreement.

The framework contract is useful for ensuring continuity of supply from one or more suppliers of a certain product that is essential for planning industrial or commercial activity. While the general terms and conditions of purchase or sale are the rules that apply to all suppliers or customers of the company. The framework contract is advisable to be concluded with essential suppliers for the continuity of business activity, in general or in relation to a particular project.

What I am talking about in this article:

- What is the supply framework agreement?

- What is the function of the supply framework agreement?

- The difference with the general conditions of sale or purchase

- When to enter a purchase framework agreement?

- When is it beneficial to conclude a sales framework agreement?

- The content of the supply framework agreement

- Price revision clause and hardship

- Delivery terms in the supply framework agreement

- The Force Majeure clause in international sales contracts

- International sales: applicable law and dispute resolution arrangements

What is a framework supply agreement?

It is an agreement that regulates a series of future sales and purchases between two parties (customer and supplier), which will take place over a certain period.

It is therefore referred to as a “framework agreement” because it is an agreement that establishes the rules of a future series of sales and purchase contracts, determining their primary elements (such as the price, the volumes of products to be sold and purchased, the delivery terms of the products, and the duration of the contract).

After concluding the framework agreement, the parties will exchange orders and order confirmations, entering a series of autonomous sales contracts without re-discussing the covenants already defined in the framework agreement.

Depending on one’s point of view, this agreement is also called a sales framework agreement (if the seller/supplier uses it) or a purchasing framework agreement (if the customer proposes it).

What is the function of the framework supply agreement?

It is helpful to arrange a framework agreement in all cases where the parties intend to proceed with a series of purchases/sales of products over time and are interested in giving stability to the commercial agreement by determining its main elements.

In particular, the purchase framework agreement may be helpful to a company that wishes to ensure continuity of supply from one or more suppliers of a specific product that is essential for planning its industrial or commercial activity (raw material, semi-finished product, component).

By concluding the framework agreement, the company can obtain, for example, a commitment from the supplier to supply a particular minimum volume of products, at a specific price, with agreed terms and technical specifications, for a certain period.

This agreement is also beneficial, at the same time, to the seller/supplier, which can plan sales for that period and organize, in turn, the supply chain that enables it to procure the raw materials and components necessary to produce the products.

What is the difference between a purchase or sales framework agreement and the general terms and conditions?

Whereas the framework agreement is an agreement that is used with one or more suppliers for a specific product and a certain time frame, determining the essential elements of future contracts, the general purchase (or sales) conditions are the rules that apply to all the company’s suppliers (or customers).

The first agreement, therefore, is negotiated and defined on a case-by-case basis. At the same time, the general conditions are prepared unilaterally by the company, and the customers or suppliers (depending on whether they are sales or purchase conditions) adhere to and accept that the general conditions apply to the individual order and/or future contracts.

The two agreements might also co-exist: in that case; it is a good idea to specify which contract should prevail in the event of a discrepancy between the different provisions (usually, this hierarchy is envisaged, ranging from the special to the general: order – order confirmation; framework agreement; general terms and conditions of purchase).

When is it important to conclude a purchase framework agreement?

It is beneficial to conclude this agreement when dealing with a mono-supplier or a supplier that would be very difficult to replace if it stopped selling products to the purchasing company.

The risks one aims to avoid or diminish are so-called stock-outs, i.e., supply interruptions due to the supplier’s lack of availability of products or because the products are available, but the parties cannot agree on the delivery time or sales price.

Another result that can be achieved is to bind a strategic supplier for a certain period by agreeing that it will reserve an agreed share of production for the buyer on predetermined terms and conditions and avoid competition with offers from third parties interested in the products for the duration of the agreement.

When is it helpful to conclude a sales framework agreement?

This agreement allows the seller/supplier to plan sales to a particular customer and thus to plan and organize its production and logistical capacity for the agreed period, avoiding extra costs or delays.

Planning sales also makes it possible to correctly manage financial obligations and cash flows with a medium-term vision, harmonizing commitments and investments with the sales to one’s customers.

What is the content of the supply framework agreement?

There is no standard model of this agreement, which originated from business practice to meet the requirements indicated above.

Generally, the agreement provides for a fixed period (e.g., 12 months) in which the parties undertake to conclude a series of purchases and sales of products, determining the price and terms of supply and the main covenants of future sales contracts.

The most important clauses are:

- the identification of products and technical specifications (often identified in an annex)

- the minimum/maximum volume of supplies

- the possible obligation to purchase/sell a minimum/maximum volume of products

- the schedule of supplies

- the delivery times

- the determination of the price and the conditions for its possible modification (see also the next paragraph)

- impediments to performance (Force Majeure)

- cases of Hardship

- penalties for delay or non-performance or for failure to achieve the agreed volumes

- the hierarchy between the framework agreement and the orders and any other contracts between the parties

- applicable law and dispute resolution (especially in international agreements)

How to handle price revision in a supply contract?

A crucial clause, especially in times of strong fluctuations in the prices of raw materials, transport, and energy, is the price revision clause.

In the absence of an agreement on this issue, the parties bear the risk of a price increase by undertaking to respect the conditions initially agreed upon; except in exceptional cases (where the fluctuation is strong, affects a short period, and is caused by unforeseeable events), it isn’t straightforward to invoke the supervening excessive onerousness, which allows renegotiating the price, or the contract to be terminated.

To avoid the uncertainty generated by price fluctuations, it is advisable to agree in the contract on the mechanisms for revising the price (e.g., automatic indexing following the quotation of raw materials). The so-called Hardship or Excessive Onerousness clause establishes what price fluctuation limits are accepted by the parties and what happens if the variations go beyond these limits, providing for the obligation to renegotiate the price or the termination of the contract if no agreement is reached within a certain period.

How to manage delivery terms in a supply agreement?

Another fundamental pact in a medium to long-term supply relationship concerns delivery terms. In this case, it is necessary to reconcile the purchaser’s interest in respecting the agreed dates with the supplier’s interest in avoiding claims for damages in the event of a delay, especially in the case of sales requiring intercontinental transport.

The first thing to be clarified in this regard concerns the nature of delivery deadlines: are they essential or indicative? In the first case, the party affected has the right to terminate (i.e., wind up) the agreement in the event of non-compliance with the term; in the second case, due diligence, information, and timely notification of delays may be required, whereas termination is not a remedy that may be automatically invoked in the event of a delay.

A useful instrument in this regard is the penalty clause: with this covenant, it is established that for each day/week/month of delay, a sum of money is due by way of damages in favor of the party harmed by the delay.

If quantified correctly and not excessively, the penalty is helpful for both parties because it makes it possible to predict the damages that may be claimed for the delay, quantifying them in a fair and determined sum. Consequently, the seller is not exposed to claims for damages related to factors beyond his control. At the same time, the buyer can easily calculate the compensation for the delay without the need for further proof.

The same mechanism, among other things, may be adopted to govern the buyer’s delay in accepting delivery of the goods.

Finally, it is a good idea to specify the limit of the penalty (e.g.,10 percent of the price of the goods) and a maximum period of grace for the delay, beyond which the party concerned is entitled to terminate the contract by retaining the penalty.

The Force Majeure clause in international sales contracts

A situation that is often confused with excessive onerousness, but is, in fact, quite different, is that of Force Majeure, i.e., the supervening impossibility of performance of the contractual obligation due to any event beyond the reasonable control of the party affected, which could not have been reasonably foreseen and the effects of which cannot be overcome by reasonable efforts.

The function of this clause is to set forth clearly when the parties consider that Force Majeure may be invoked, what specific events are included (e.g., a lock-down of the production plant by order of the authority), and what are the consequences for the parties’ obligations (e.g., suspension of the obligation for a certain period, as long as the cause of impossibility of performance lasts, after which the party affected by performance may declare its intention to dissolve the contract).

If the wording of this clause is general (as is often the case), the risk is that it will be of little use; it is also advisable to check that the regulation of force majeure complies with the law applicable to the contract (here an in-depth analysis indicating the regime provided for by 42 national laws).

Applicable law and dispute resolution clauses

Suppose the customer or supplier is based abroad. In that case, several significant differences must be borne in mind: the first is the agreement’s language, which must be intelligible to the foreign party, therefore usually in English or another language familiar to the parties, possibly also in two languages with parallel text.

The second issue concerns the applicable law, which should be expressly indicated in the agreement. This subject matter is vast, and here we can say that the decision on the applicable law must be made on a case-by-case basis, intentionally: in fact, it is not always convenient to recall the application of the law of one’s own country.

In most international sales contracts, the 1980 Vienna Convention on the International Sale of Goods (“CISG”) applies, a uniform law that is balanced, clear, and easy to understand. Therefore, it is not advisable to exclude it.

Finally, in a supply framework agreement with an international supplier, it is important to identify the method of dispute resolution: no solution fits all. Choosing a country’s jurisdiction is not always the right decision (indeed, it can often prove counterproductive).

Summary

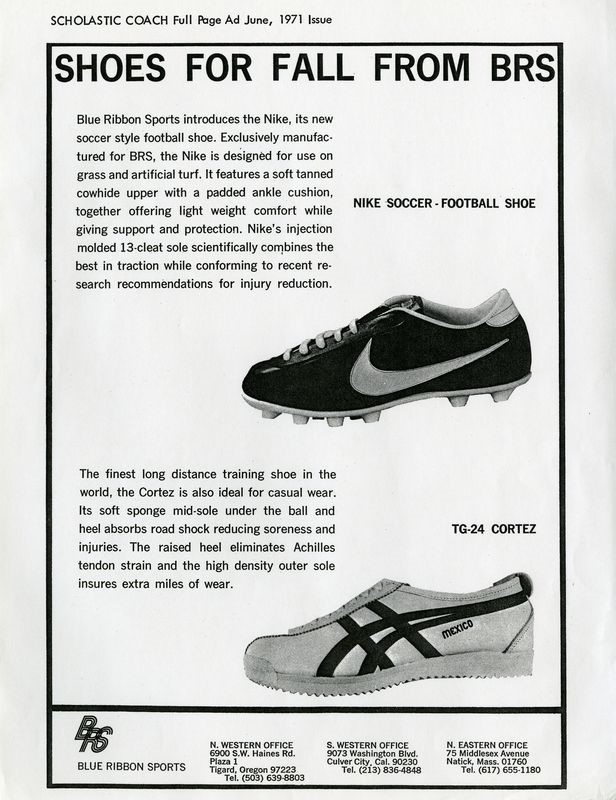

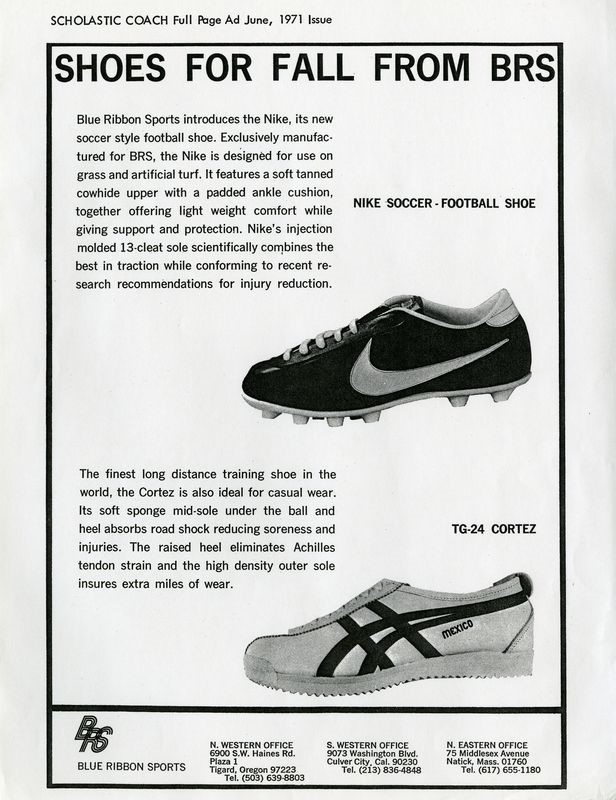

Phil Knight, the founder of Nike, imported the Japanese brand Onitsuka Tiger into the US market in 1964 and quickly gained a 70% share. When Knight learned Onitsuka was looking for another distributor, he created the Nike brand. This led to two lawsuits between the two companies, but Nike eventually won and became the most successful sportswear brand in the world. This article looks at the lessons to be learned from the dispute, such as how to negotiate an international distribution agreement, contractual exclusivity, minimum turnover clauses, duration of the contract, ownership of trademarks, dispute resolution clauses, and more.

What I talk about in this article

- The Blue Ribbon vs. Onitsuka Tiger dispute and the birth of Nike

- How to negotiate an international distribution agreement

- Contractual exclusivity in a commercial distribution agreement

- Minimum Turnover clauses in distribution contracts

- Duration of the contract and the notice period for termination

- Ownership of trademarks in commercial distribution contracts

- The importance of mediation in international commercial distribution agreements

- Dispute resolution clauses in international contracts

- How we can help you

The Blue Ribbon vs Onitsuka Tiger dispute and the birth of Nike

Why is the most famous sportswear brand in the world Nike and not Onitsuka Tiger?

Shoe Dog is the biography of the creator of Nike, Phil Knight: for lovers of the genre, but not only, the book is really very good and I recommend reading it.

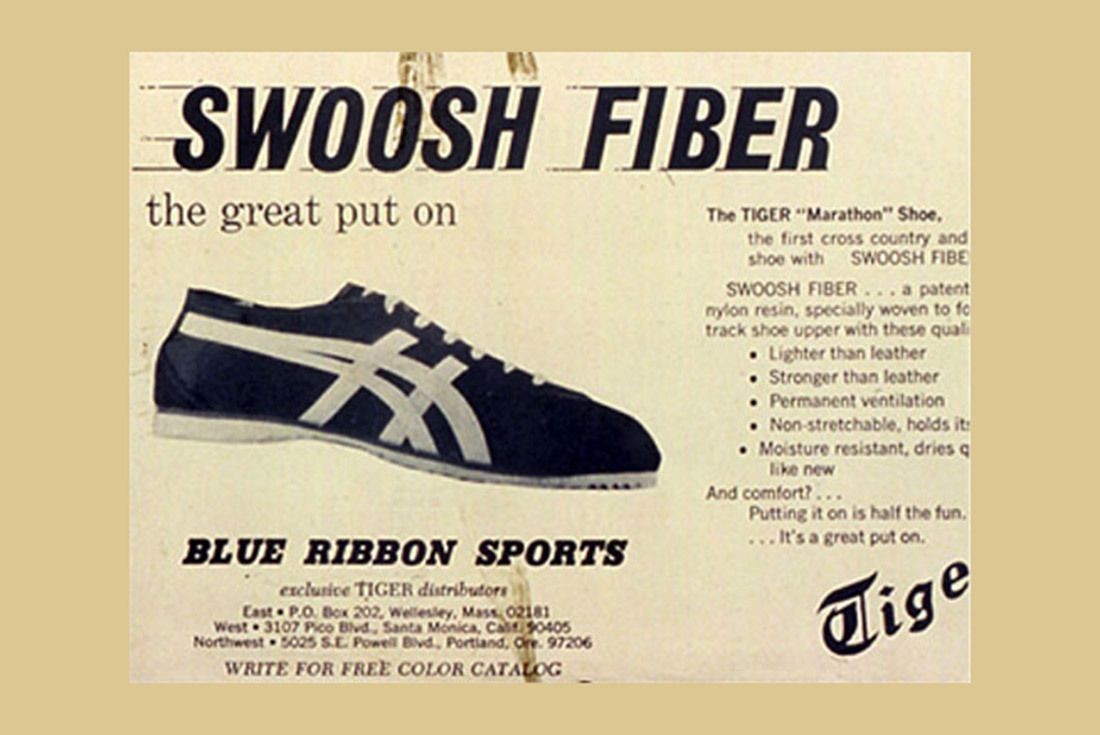

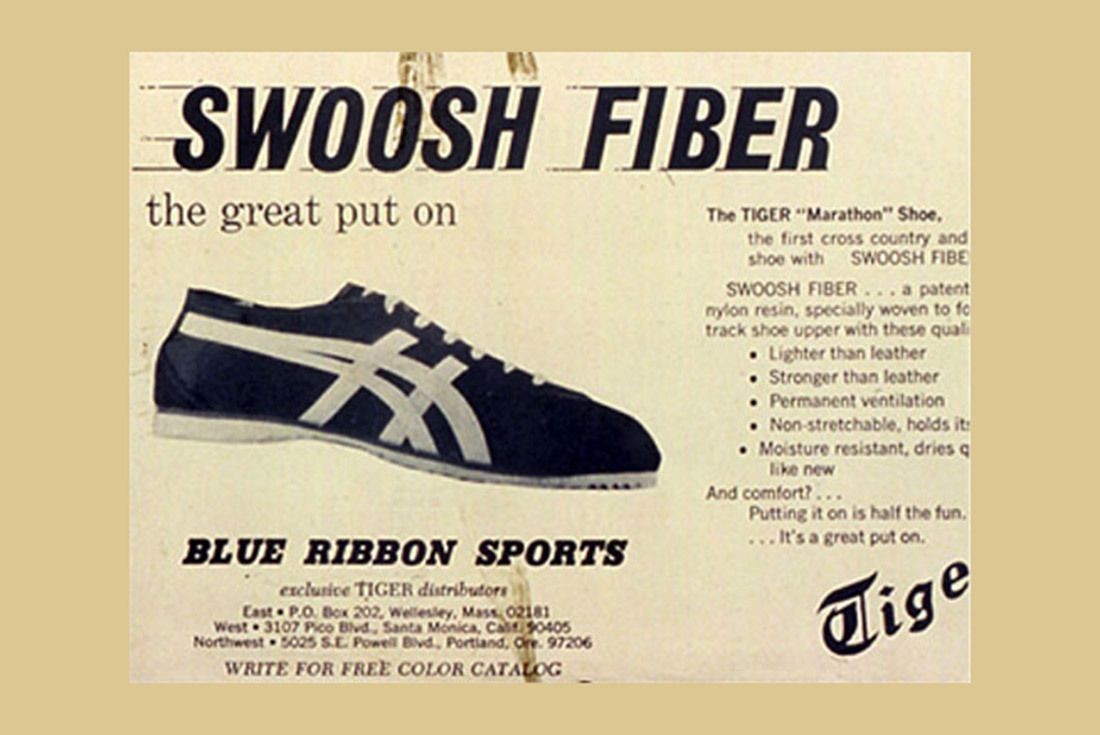

Moved by his passion for running and intuition that there was a space in the American athletic shoe market, at the time dominated by Adidas, Knight was the first, in 1964, to import into the U.S. a brand of Japanese athletic shoes, Onitsuka Tiger, coming to conquer in 6 years a 70% share of the market.

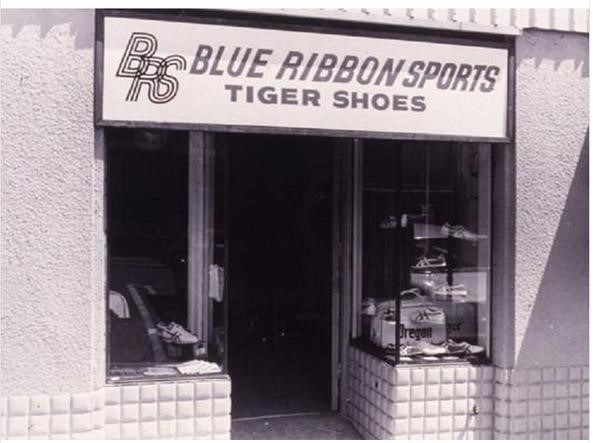

The company founded by Knight and his former college track coach, Bill Bowerman, was called Blue Ribbon Sports.

The business relationship between Blue Ribbon-Nike and the Japanese manufacturer Onitsuka Tiger was, from the beginning, very turbulent, despite the fact that sales of the shoes in the U.S. were going very well and the prospects for growth were positive.

When, shortly after having renewed the contract with the Japanese manufacturer, Knight learned that Onitsuka was looking for another distributor in the U.S., fearing to be cut out of the market, he decided to look for another supplier in Japan and create his own brand, Nike.

Upon learning of the Nike project, the Japanese manufacturer challenged Blue Ribbon for violation of the non-competition agreement, which prohibited the distributor from importing other products manufactured in Japan, declaring the immediate termination of the agreement.

In turn, Blue Ribbon argued that the breach would be Onitsuka Tiger’s, which had started meeting other potential distributors when the contract was still in force and the business was very positive.

This resulted in two lawsuits, one in Japan and one in the U.S., which could have put a premature end to Nike’s history.

Fortunately (for Nike) the American judge ruled in favor of the distributor and the dispute was closed with a settlement: Nike thus began the journey that would lead it 15 years later to become the most important sporting goods brand in the world.

Let’s see what Nike’s history teaches us and what mistakes should be avoided in an international distribution contract.

How to negotiate an international commercial distribution agreement

In his biography, Knight writes that he soon regretted tying the future of his company to a hastily written, few-line commercial agreement at the end of a meeting to negotiate the renewal of the distribution contract.

What did this agreement contain?

The agreement only provided for the renewal of Blue Ribbon’s right to distribute products exclusively in the USA for another three years.

It often happens that international distribution contracts are entrusted to verbal agreements or very simple contracts of short duration: the explanation that is usually given is that in this way it is possible to test the commercial relationship, without binding too much to the counterpart.

This way of doing business, though, is wrong and dangerous: the contract should not be seen as a burden or a constraint, but as a guarantee of the rights of both parties. Not concluding a written contract, or doing so in a very hasty way, means leaving without clear agreements fundamental elements of the future relationship, such as those that led to the dispute between Blue Ribbon and Onitsuka Tiger: commercial targets, investments, ownership of brands.

If the contract is also international, the need to draw up a complete and balanced agreement is even stronger, given that in the absence of agreements between the parties, or as a supplement to these agreements, a law with which one of the parties is unfamiliar is applied, which is generally the law of the country where the distributor is based.

Even if you are not in the Blue Ribbon situation, where it was an agreement on which the very existence of the company depended, international contracts should be discussed and negotiated with the help of an expert lawyer who knows the law applicable to the agreement and can help the entrepreneur to identify and negotiate the important clauses of the contract.

Territorial exclusivity, commercial objectives and minimum turnover targets

The first reason for conflict between Blue Ribbon and Onitsuka Tiger was the evaluation of sales trends in the US market.

Onitsuka argued that the turnover was lower than the potential of the U.S. market, while according to Blue Ribbon the sales trend was very positive, since up to that moment it had doubled every year the turnover, conquering an important share of the market sector.

When Blue Ribbon learned that Onituska was evaluating other candidates for the distribution of its products in the USA and fearing to be soon out of the market, Blue Ribbon prepared the Nike brand as Plan B: when this was discovered by the Japanese manufacturer, the situation precipitated and led to a legal dispute between the parties.

The dispute could perhaps have been avoided if the parties had agreed upon commercial targets and the contract had included a fairly standard clause in exclusive distribution agreements, i.e. a minimum sales target on the part of the distributor.

In an exclusive distribution agreement, the manufacturer grants the distributor strong territorial protection against the investments the distributor makes to develop the assigned market.

In order to balance the concession of exclusivity, it is normal for the producer to ask the distributor for the so-called Guaranteed Minimum Turnover or Minimum Target, which must be reached by the distributor every year in order to maintain the privileged status granted to him.

If the Minimum Target is not reached, the contract generally provides that the manufacturer has the right to withdraw from the contract (in the case of an open-ended agreement) or not to renew the agreement (if the contract is for a fixed term) or to revoke or restrict the territorial exclusivity.

In the contract between Blue Ribbon and Onitsuka Tiger, the agreement did not foresee any targets (and in fact the parties disagreed when evaluating the distributor’s results) and had just been renewed for three years: how can minimum turnover targets be foreseen in a multi-year contract?

In the absence of reliable data, the parties often rely on predetermined percentage increase mechanisms: +10% the second year, + 30% the third, + 50% the fourth, and so on.

The problem with this automatism is that the targets are agreed without having available the real data on the future trend of product sales, competitors’ sales and the market in general, and can therefore be very distant from the distributor’s current sales possibilities.

For example, challenging the distributor for not meeting the second or third year’s target in a recessionary economy would certainly be a questionable decision and a likely source of disagreement.

It would be better to have a clause for consensually setting targets from year to year, stipulating that targets will be agreed between the parties in the light of sales performance in the preceding months, with some advance notice before the end of the current year. In the event of failure to agree on the new target, the contract may provide for the previous year’s target to be applied, or for the parties to have the right to withdraw, subject to a certain period of notice.

It should be remembered, on the other hand, that the target can also be used as an incentive for the distributor: it can be provided, for example, that if a certain turnover is achieved, this will enable the agreement to be renewed, or territorial exclusivity to be extended, or certain commercial compensation to be obtained for the following year.

A final recommendation is to correctly manage the minimum target clause, if present in the contract: it often happens that the manufacturer disputes the failure to reach the target for a certain year, after a long period in which the annual targets had not been reached, or had not been updated, without any consequences.

In such cases, it is possible that the distributor claims that there has been an implicit waiver of this contractual protection and therefore that the withdrawal is not valid: to avoid disputes on this subject, it is advisable to expressly provide in the Minimum Target clause that the failure to challenge the failure to reach the target for a certain period does not mean that the right to activate the clause in the future is waived.

The notice period for terminating an international distribution contract

The other dispute between the parties was the violation of a non-compete agreement: the sale of the Nike brand by Blue Ribbon, when the contract prohibited the sale of other shoes manufactured in Japan.

Onitsuka Tiger claimed that Blue Ribbon had breached the non-compete agreement, while the distributor believed it had no other option, given the manufacturer’s imminent decision to terminate the agreement.

This type of dispute can be avoided by clearly setting a notice period for termination (or non-renewal): this period has the fundamental function of allowing the parties to prepare for the termination of the relationship and to organize their activities after the termination.

In particular, in order to avoid misunderstandings such as the one that arose between Blue Ribbon and Onitsuka Tiger, it can be foreseen that during this period the parties will be able to make contact with other potential distributors and producers, and that this does not violate the obligations of exclusivity and non-competition.

In the case of Blue Ribbon, in fact, the distributor had gone a step beyond the mere search for another supplier, since it had started to sell Nike products while the contract with Onitsuka was still valid: this behavior represents a serious breach of an exclusivity agreement.

A particular aspect to consider regarding the notice period is the duration: how long does the notice period have to be to be considered fair? In the case of long-standing business relationships, it is important to give the other party sufficient time to reposition themselves in the marketplace, looking for alternative distributors or suppliers, or (as in the case of Blue Ribbon/Nike) to create and launch their own brand.

The other element to be taken into account, when communicating the termination, is that the notice must be such as to allow the distributor to amortize the investments made to meet its obligations during the contract; in the case of Blue Ribbon, the distributor, at the express request of the manufacturer, had opened a series of mono-brand stores both on the West and East Coast of the U.S.A..

A closure of the contract shortly after its renewal and with too short a notice would not have allowed the distributor to reorganize the sales network with a replacement product, forcing the closure of the stores that had sold the Japanese shoes up to that moment.

Generally, it is advisable to provide for a notice period for withdrawal of at least 6 months, but in international distribution contracts, attention should be paid, in addition to the investments made by the parties, to any specific provisions of the law applicable to the contract (here, for example, an in-depth analysis for sudden termination of contracts in France) or to case law on the subject of withdrawal from commercial relations (in some cases, the term considered appropriate for a long-term sales concession contract can reach 24 months).

Finally, it is normal that at the time of closing the contract, the distributor is still in possession of stocks of products: this can be problematic, for example because the distributor usually wishes to liquidate the stock (flash sales or sales through web channels with strong discounts) and this can go against the commercial policies of the manufacturer and new distributors.

In order to avoid this type of situation, a clause that can be included in the distribution contract is that relating to the producer’s right to repurchase existing stock at the end of the contract, already setting the repurchase price (for example, equal to the sale price to the distributor for products of the current season, with a 30% discount for products of the previous season and with a higher discount for products sold more than 24 months previously).

Trademark Ownership in an International Distribution Agreement

During the course of the distribution relationship, Blue Ribbon had created a new type of sole for running shoes and coined the trademarks Cortez and Boston for the top models of the collection, which had been very successful among the public, gaining great popularity: at the end of the contract, both parties claimed ownership of the trademarks.

Situations of this kind frequently occur in international distribution relationships: the distributor registers the manufacturer’s trademark in the country in which it operates, in order to prevent competitors from doing so and to be able to protect the trademark in the case of the sale of counterfeit products; or it happens that the distributor, as in the dispute we are discussing, collaborates in the creation of new trademarks intended for its market.

At the end of the relationship, in the absence of a clear agreement between the parties, a dispute can arise like the one in the Nike case: who is the owner, producer or distributor?

In order to avoid misunderstandings, the first advice is to register the trademark in all the countries in which the products are distributed, and not only: in the case of China, for example, it is advisable to register it anyway, in order to prevent third parties in bad faith from taking the trademark (for further information see this post on Legalmondo).

It is also advisable to include in the distribution contract a clause prohibiting the distributor from registering the trademark (or similar trademarks) in the country in which it operates, with express provision for the manufacturer’s right to ask for its transfer should this occur.

Such a clause would have prevented the dispute between Blue Ribbon and Onitsuka Tiger from arising.

The facts we are recounting are dated 1976: today, in addition to clarifying the ownership of the trademark and the methods of use by the distributor and its sales network, it is advisable that the contract also regulates the use of the trademark and the distinctive signs of the manufacturer on communication channels, in particular social media.

It is advisable to clearly stipulate that the manufacturer is the owner of the social media profiles, of the content that is created, and of the data generated by the sales, marketing and communication activity in the country in which the distributor operates, who only has the license to use them, in accordance with the owner’s instructions.

In addition, it is a good idea for the agreement to establish how the brand will be used and the communication and sales promotion policies in the market, to avoid initiatives that may have negative or counterproductive effects.

The clause can also be reinforced with the provision of contractual penalties in the event that, at the end of the agreement, the distributor refuses to transfer control of the digital channels and data generated in the course of business.

Mediation in international commercial distribution contracts

Another interesting point offered by the Blue Ribbon vs. Onitsuka Tiger case is linked to the management of conflicts in international distribution relationships: situations such as the one we have seen can be effectively resolved through the use of mediation.

This is an attempt to reconcile the dispute, entrusted to a specialized body or mediator, with the aim of finding an amicable agreement that avoids judicial action.

Mediation can be provided for in the contract as a first step, before the eventual lawsuit or arbitration, or it can be initiated voluntarily within a judicial or arbitration procedure already in progress.

The advantages are many: the main one is the possibility to find a commercial solution that allows the continuation of the relationship, instead of just looking for ways for the termination of the commercial relationship between the parties.

Another interesting aspect of mediation is that of overcoming personal conflicts: in the case of Blue Ribbon vs. Onitsuka, for example, a decisive element in the escalation of problems between the parties was the difficult personal relationship between the CEO of Blue Ribbon and the Export manager of the Japanese manufacturer, aggravated by strong cultural differences.

The process of mediation introduces a third figure, able to dialogue with the parts and to guide them to look for solutions of mutual interest, that can be decisive to overcome the communication problems or the personal hostilities.

For those interested in the topic, we refer to this post on Legalmondo and to the replay of a recent webinar on mediation of international conflicts.

Dispute resolution clauses in international distribution agreements

The dispute between Blue Ribbon and Onitsuka Tiger led the parties to initiate two parallel lawsuits, one in the US (initiated by the distributor) and one in Japan (rooted by the manufacturer).

This was possible because the contract did not expressly foresee how any future disputes would be resolved, thus generating a very complicated situation, moreover on two judicial fronts in different countries.

The clauses that establish which law applies to a contract and how disputes are to be resolved are known as “midnight clauses“, because they are often the last clauses in the contract, negotiated late at night.

They are, in fact, very important clauses, which must be defined in a conscious way, to avoid solutions that are ineffective or counterproductive.

How we can help you

The construction of an international commercial distribution agreement is an important investment, because it sets the rules of the relationship between the parties for the future and provides them with the tools to manage all the situations that will be created in the future collaboration.

It is essential not only to negotiate and conclude a correct, complete and balanced agreement, but also to know how to manage it over the years, especially when situations of conflict arise.

Legalmondo offers the possibility to work with lawyers experienced in international commercial distribution in more than 60 countries: write us your needs.

A case recently decided by the Italian Supreme Court clarifies what the risks are for those who sell their products abroad without having paid adequate attention to the legal part of the contract (Order, Sec. 2, No. 36144 of 2022, published 12/12/2022).

Why it’s important: in contracts, care must be taken not only with what is written, but also with what is not written, otherwise there is a risk that implied warranties of merchantability will apply, which may make the product unsuitable for use, even if it conforms to the technical specifications agreed upon in the contract.

The international sales contract and the first instance decision

A German company had sued an Italian company in Italy (Court of Chieti) to have it ordered to pay the sales price of two invoices for supplies of goods (steel).

The Italian purchasing company had defended itself by claiming that the two invoices had been deliberately not paid, due to the non-conformity of three previous deliveries by the same German seller. It then counterclaimed for a finding of defects and a reduction in the price, to be set off against the other party’s claim, as well as damages.

In the first instance, the Court of Chieti had partially granted both the German seller’s demand for payment (for about half of the claim) and the buyer’s counterclaim.

The court-appointed technical expertise had found that the steel supplied by the seller, while conforming to the agreed data sheet, had a very low silicon value compared to the values at other manufacturers’ steel; however, the trial judge ruled out this as a genuine defect.

The judgment of appeal